Read More

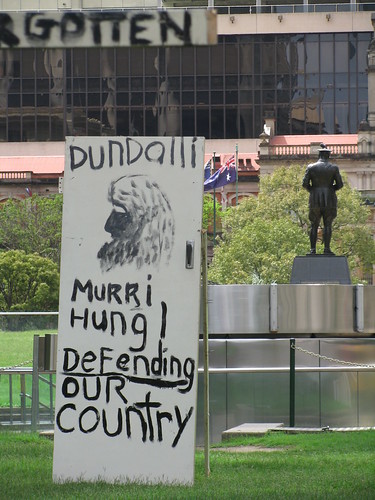

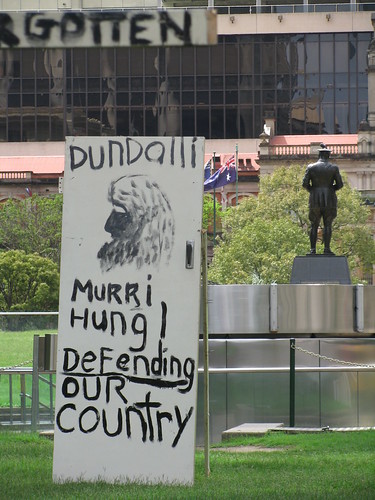

Dundalli Sketch by Sylvester Diggles, 1854

was an Aboriginal leader and fighter from the Dalla people of the Blackall Ranges who was eventually adopted by the fearsome Djindubarri people of Bribie Island in the 1840’s.

He was convicted of the murder of Andrew Gregor and Mary Shannon in 1846. People much more qualified than I have described how the trial and conviction of Dundalli were unjust. I won’t regurgitate those arguments here, but if you’re interested, you might like to read some articles by Dr Libby Connors and Dr Dale Kerwin.

His execution was particularly gruesome. The hangman botched it while his distraught relatives looked on in horror from the hillside on what is now Wickham Terrace. The rope was too long, at the drop Dundalli actually landed on his coffin, and the hangman had to bend his legs and drag down on them to kill him.

This happened exactly 156 years ago today. So I decided to honour Dundalli by cycling into the city to the GPO and back (about 80km), stopping by “Yorks Hollow” – an important traditional camping ground for Aborigines prior to European settlement.

Yorks Hollow used to cover most of what is Victoria Park Golf Course and the Exhibition Grounds. Today it’s little more than a small park beside the busy Inner City Bypass motorway. But it’s still a beautiful park – especially when you pause to think about what it was.

In her book, “Tom Petrie’s Reminiscences of Early Queensland”, Constance Campbell Petrie says of it:

Another big “tulan” or fight, Father remembers at

York’s Hollow (the Exhibition). He and his brother Walter

were standing looking on, when a fighting boomerang thrown

from the crowd circled round, and travelling in the direction

of the brothers, struck Walter Petrie on the cheek, causing

a deep flesh wound. The gins and blacks of the Brisbane

tribe commenced to cry about this, and said that the weapon

had come from the Bribie blacks’ side, and that they were

no good, but wild fellows. The brothers went home, and the

cut was sewn up. It did not take long to heal afterwards.

At that fight there must have been about eight hundred

blacks gathered from all parts, and there were about twenty

wounded. One very fine blackfellow lost his life. His

name was “Tunbur” (maggot). In the fight he got hit

on the ankle with a waddie, and next day died from lockjaw.

They carried the remains, and crossed the creek where the

Enoggera railway bridge is now, and further on made a fire

and skiimed the body and ate it. My father knew ” Tunbur”

well; he was one of the blacks who accompanied grandfather

Petrie on his trip in search of a sample of ” bon-yi ” wood.

I was pleasantly surprised to find out someone else had the same idea and had erected some signs about Dundalli in Post Office Square across the road from the GPO. The GPO was actually built in 1871 on the site of the old Female Convict Factory.

What struck me today was the irony. Here was a war memorial on the front wall of GPO comemorating soldiers who had died for their country in the First World War, yet it was the same place a black man was killed for trying to protect his country and uphold his people’s laws.

Even the grand statue of Major General Sir William Glasgow appeared to look away in shame from the GPO and the memorial posters there.

The trouble is we often become emotionally immune to irony, even though it can sometimes highlight painful truths. I’m glad I did what the sign said, and walked in his tracks.